Leonardo Da Vinci

In 1452, Leonardo Da Vinci was born in an Italian town called Vinci. He lived in a time period called the Renaissance, when everyone was interested in art. Even though Da Vinci was a great artist, he became famous because of all the other things he could do. He was a sculptor, a scientist, an inventor, an architect, a musician, and a mathematician. When he was twenty, he helped his teacher finish a painting called The Baptism of Christ. When he was thirty, he moved to Milan. That is where he painted most of his pictures. DaVinci's paintings were done in the Realist style.

Madonna and Child

The Virgin of the Rocks

The Last Supper

The upper room of the Last Supper

Marc Chagall

Marc Chagall was born on July 7, 1887 in Vitebsk, Russia. In 1932 he moved to France. He lived in the United States from 1941 to 1948, and then returned to France. He died in France on March 28. 1985.

In 1452, Leonardo Da Vinci was born in an Italian town called Vinci. He lived in a time period called the Renaissance, when everyone was interested in art. Even though Da Vinci was a great artist, he became famous because of all the other things he could do. He was a sculptor, a scientist, an inventor, an architect, a musician, and a mathematician. When he was twenty, he helped his teacher finish a painting called The Baptism of Christ. When he was thirty, he moved to Milan. That is where he painted most of his pictures. DaVinci's paintings were done in the Realist style.

Madonna and Child

The Virgin of the Rocks

The Last Supper

The upper room of the Last Supper

Marc Chagall

Marc Chagall was born on July 7, 1887 in Vitebsk, Russia. In 1932 he moved to France. He lived in the United States from 1941 to 1948, and then returned to France. He died in France on March 28. 1985.

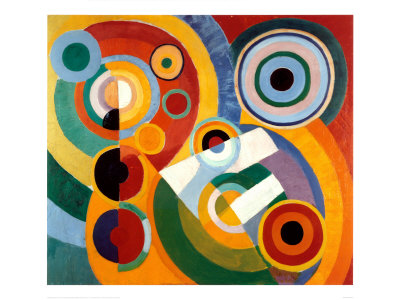

His painting styles are Expressionism and Cubism. In his paintings, he often painted violinists because he played the violin and also in memory of his uncle, who also played. He was also famous for his paintings of Russian-Jewish villages.

I and the Village

The Praying Jew

Over Vitebsk

The Violinist